That’s the only existing picture of Victor Bonderoff I could find online; I have none of my own. This had to be the 70s. Or maybe it’s the 80s. I really don’t know.

I hadn’t thought about Victor in several years.

Our last bit of communication was back in the summer of 2018, and it hadn’t been too great. In fact, it had been extremely negative, full of hurt and crossed signals and confusion and the sad understanding that we really shouldn’t have bothered resurrecting a relationship that had run its course by mid-2016. That year, we had severed something that was tiring and intense for both of us and stressful for me, but in my loneliness, vulnerability, and increasingly unstable mental state, I had contacted him again two years later and we gave it about a month before I proved unable to sustain anything requiring a solid, sound psychological foundation.

Also, people come into and out of your life at certain intervals, perhaps for certain purposes or to help you get through particular eras, and aren’t necessarily meant to stick around indefinitely. I’d like to think that’s how things were between Victor and me, because it’s the only way I can make sense of everything, and the only way I can put my conscience to rest.

But in early November of last year (can’t believe we’re already saying “last year,” despite it being less than two weeks into 2026), I was staring at one of his two paintings that are framed and hung on my bedroom wall–small prints of these paintings, to be accurate–and allowed myself to entertain a curiosity about where he could be, and what he might be doing. I decided to Google him and see if there were any updates about his whereabouts or actions over the past seven years…seven years in which he quite honestly hadn’t crossed my mind much at all, mostly because I wouldn’t allow him to.

There wasn’t much that showed up online about Victor, apart from one Instagram post that caused every nerve in my body to stand at attention. It showed a photo of two hands holding up glasses, with this caption:

We’re raising a wee dram to Victor Bonderoff, a wonderful friend and artist. Rest in peace.

It was dated October 4, 2024, slightly more than a year ago, and so I reasoned that this had to be some kind of macabre Hallowe’en prank. There was no way this was actually genuine. Still, I left a message for the person who had posted this:

I looked his name up online…and saw this. I am an old friend of his. Is Victor still around??

Several weeks went by. I am rarely on Instagram, posting a single random photo perhaps once a month–if that–and completely uninterested in social media in general. I’m sure it’s something I have to embrace with forced gusto if I am to publicize and advertise my writing, and I certainly have done my reluctant best, but it’s such a nauseating form of interaction that I avoid it as much as possible.

On December 31st, I was getting ready to say dasvedanya to an extremely challenging year–an extremely challenging decade, if we’re going to be honest–and for some reason opened Instagram for the first time in a long while. I’m not sure why. I was greeted with a reply to my weeks-old inquiry from someone who appeared to be Victor’s sister:

No, he passed from cancer.

Upon reading this, I only had one thought, which I kept to myself:

Oh. Then he really is dead.

I put this information into some hard-to-reach cupboard in my mind and carried on with the rest of my day and night, pleased about a new year, and about having just turned 50, and about celebrating the survival of my 40s, which were very tenuous, unproductive, and uncertain at best; an irretrievable, utter waste and a failure at worst. Nobody has ever said I’m not hard on myself.

Painting by Victor Bonderoff

The next day, New Year’s Day, I was well-rested and looking forward to starting 2026 on a positive note. I wasn’t hung over, I wasn’t aching for some hair of the dog, I wasn’t depressed, I wasn’t pessimistic, nor was I paralyzed with anxiety over my future. I decided to reach for that mental cupboard and crack it open so I could examine the reality of Victor having died of cancer, which meant giving myself permission to go back ten years, to the summer of 2015 when we had first met, and everything we had done for nearly a year afterwards. I hadn’t revisited those days since they came to an unceremonious, pitiful end.

It was also extremely bizarre that I had learned about his death exactly ten years to the day when he and I had sat together at his Kerrisdale apartment. We had been drinking red wine and writing down our resolutions for 2016, a day after we’d gone snowshoeing at Mt. Seymour and I had lobbed an enormous snowball at the back of his head as he fearlessly trudged ahead of me. What’s more, I had just mentioned this New Year’s 2015 event and Victor’s name a mere couple of days before, December 29th, towards the end of a YouTube audio-visual ramble in which I prattled on about mental health and the futility of making promises for the new year. I hadn’t thought, never mind talked about, our NYE for ten years up until this past December 2025. What were the odds? What kind of timing was this?

Despite crying into my couch cushion for a good hour and a half, it was the oddest yet most pleasant sensation to hurtle back in time to a decade ago and flip through the mental Rolodex, slideshows, and short films of our relationship, one that was more meaningful and impactful than I had permitted myself to think about…because I hadn’t permitted myself to think about it at all for a long, long time.

It has now taken me a couple of weeks to process the hard truth of Victor no longer being on the planet. I’ve worked through and relived our relatively brief time together, when both of us were the most important people in each other’s worlds–at least, that’s how it felt to me–and when he was almost seventeen years older than me and always would be, but easily younger at heart and soul, more energetic, more mischievous, more full of life and creativity and kindness than nearly anyone I knew then and have known since. It’s impossible for me to believe he’s not around, and never will be again. It’s impossible to fathom that I won’t ever be able to email him with a heartfelt letter that he would invariably accept and respond to with warmth, because that’s the kind of guy he is. Was. That’s the kind of guy Victor Bonderoff was. I have to keep telling myself he’s in the past tense, physically, technically, but I’m lucky enough to always have him in the present whenever I want. I can let him back in anytime.

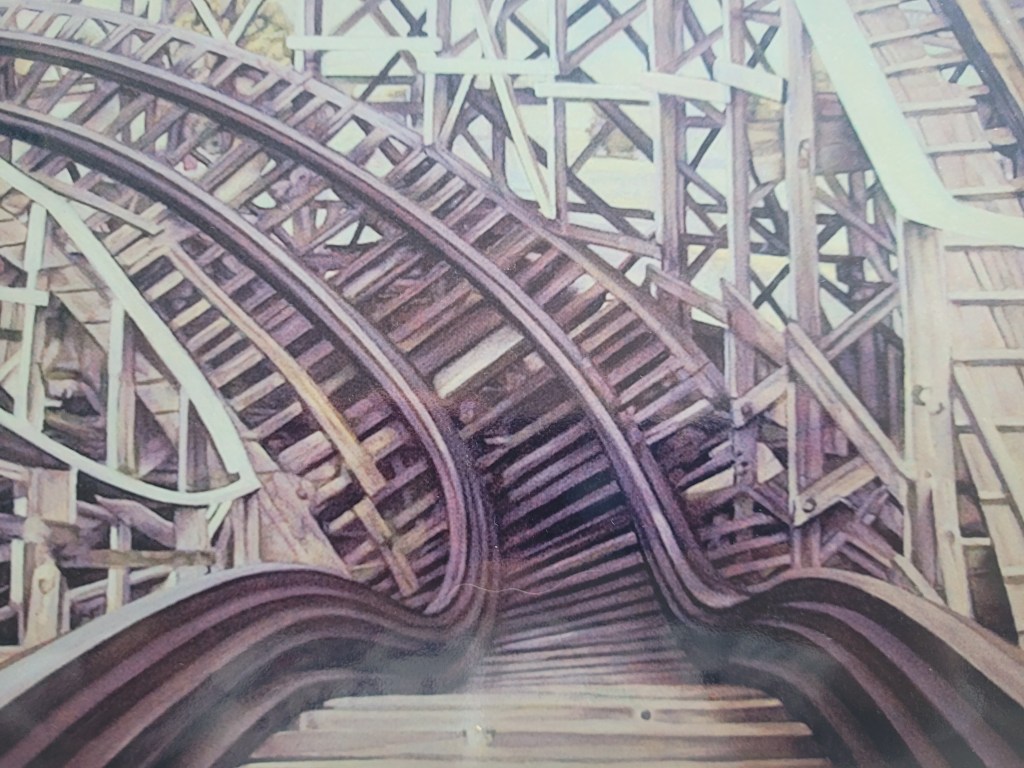

Coaster at the P.N.E., by Victor Bonderoff

* * * * *

I met him, as I mentioned above, in the summer of 2015. I still had my original, active Facebook account, and it was back when you could make “friends” with almost anyone and not be verified or have to wait around to be accepted, as is the case currently. If I recall correctly, you could collect Facebook friends as though they were stamps or postcards and not know three-quarters of them on any personal level. A couple of folks I know with obsessive tendencies just kept expanding their Facebook friends until they were well up into the three-thousand and four-thousand mark, casting a digital net and capturing virtually everyone who showed up as a recommended contact. Such desperation for invisible clout seemed absurd back then, embarrassing, even, but I suppose nowadays it’s the only real way to bring publicity to yourself and your projects. I am still enough of an analog, old-school, in-denial chick to not go this route and humiliate myself entirely; staying under the radar for now suits me just fine.

Victor was one of my Facebook friends for two reasons: he and I had the same last name apart from two vowels that were switched around; and because I remembered him from when I was a very young woman–still living at home–and seeing his name beneath hand-drawn cartoons in The Vancouver Sun. My father, himself a gifted self-taught artist, used to point out Victor’s name anytime it showed up in the daily newspaper and remark how we must surely be related to this guy since our very uncommon surnames were almost identical. When Victor somehow showed up one day as a recommended friend for me, I added him to my Facebook collection.

In the summer of 2015 I had been living in the West End again for several months, I had just started teaching ESL at what would, unbeknownst to me, be the last exploitative language school I’d ever work for in my life, and I was just starting my slow, pathetic, foggy spiral down into serious alcohol dependency and abuse. I was technically in a relationship, except that relationship had already shown itself to be dysfunctional and essentially devoid of all affection. To say I wasn’t approaching my 40s with a contented lifestyle and a rock-solid foundation is fairly obvious, but I was still functional, capable of seeking adventure, and not yet swan-diving into voluntary obliteration.

For some reason, I sent Victor Bonderoff a message asking if he wanted to meet up. I’m not sure why. He wasn’t active on Facebook, he never commented on or “liked” the few things I posted, he was one of a few hundred people I was connected to on that medium, but something compelled me to reach out and see if he wanted to grab a coffee. Curiosity, boredom, boldness, or d) all of the above, but I suppose I wanted to finally meet the fella with whom I shared an almost-identical surname that I’d taken notice of since I was a teenager.

I don’t have access to that old Facebook account at all anymore, so I can’t go back and check our exchange, but I do recall he calmly replied in the affirmative, asking where I wanted to meet.

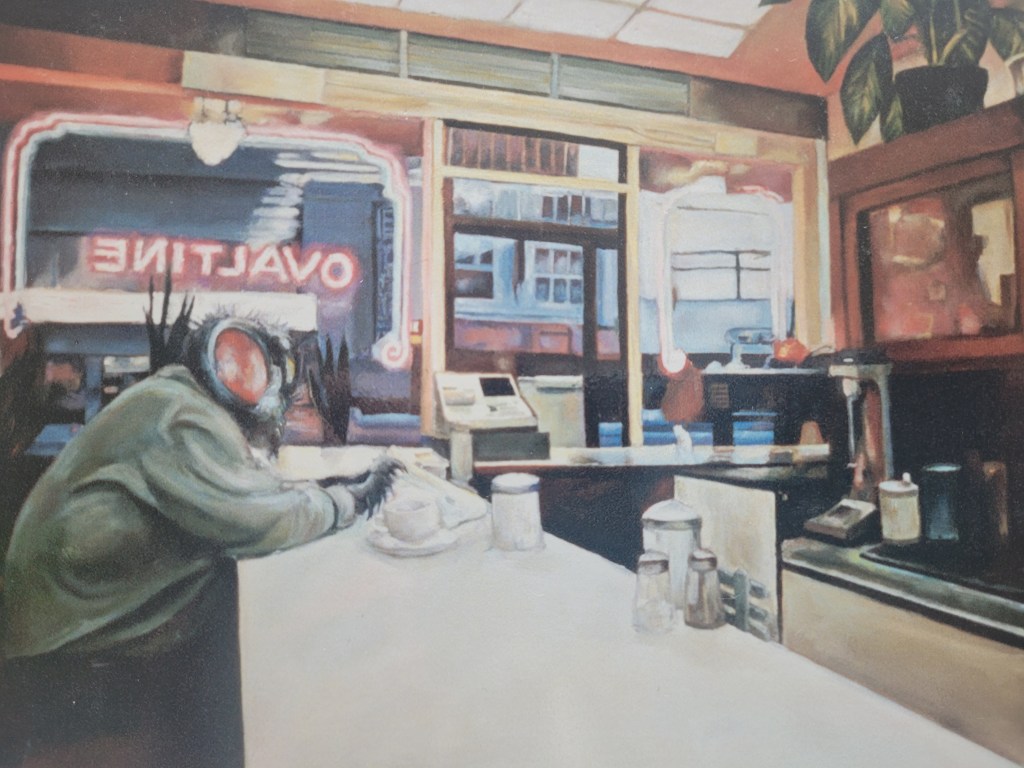

Ovaltine Cafe, by Victor Bonderoff

Feeling selfish and unwilling to go any sort of distance, I replied that I wanted to meet at Melriches, the best coffee shop in the West End (it really is) that also happens to be only a few dozen metres from the front door of my apartment building. The place is so groovy, they don’t even have a website, nor have they updated their blog since 2010. They don’t need to, you see: Melriches has remained the same for absolutely decades, and have thrived on reputation and quality alone. They eschew apps and still use manual punch-cards with each purchase so you can eventually get a free coffee, which goes with my wholly analog lifestyle.

(I was not paid or sponsored by Melriches for this tip of the hat.)

“Melriches,” I recall him writing back, “is my go-to coffee shop when I’m in the West End.” This was promising. He was clearly tasteful and discerning.

We met on what I recall was a Wednesday evening in August, and prior to meeting up with him I unnecessarily fortified myself with a few shots of vodka. His small Facebook profile picture was clear enough to give me an idea of who and what to look for. I walked into the modest coffeehouse and there he was, poker-faced and seated at a table, wearing what I recall to be a button-down shirt with the sleeves rolled up and a paisley vest. He had giant brown eyes with the sort of eyelashes that women spend piles of money to achieve artificially, and even though it took some effort to get him to finally ease up around me, once he eventually flashed me a grin, he looked startlingly similar to Willem Dafoe. He was compact, fit, elfin, and adorable.

I don’t remember what we talked about, thanks to having dulled my senses with liquor beforehand, but I do recall him being fairly standoffish and aloof, which set me off on an inquisition; as I told him later, “I figured the best defense is offense, so I interrogated the shit out of you.” I also noted that Melriches was licensed, so I suggested we each grab a glass of red wine, my treat, in order to both sustain my alcoholic cruising altitude, and to hopefully bring Victor down to a level of relaxation. I would soon learn that he was anything but uptight and severe; I would never again experience this rather rigid version of Victor.

…which I’m sure I helped dissolve when I yoinked him into the alley behind Melriches and began smooching him, this perfect stranger with the same-ish Doukhobor surname as my own.

This sort of move had been standard operating procedure for a long time, you see: it was par for the course for me to get considerably tipsy and concurrently randy. I had also been quite deprived of satisfying physical contact for longer than was reasonable, and there was some gleam in Victor’s gaze that told me he would be up for it; some kind of subtle chemistry between us I could detect despite not being sober. So we made out like pubescents in full view of the still-open laundromat to my right and then went our separate ways, not even exchanging numbers.

The next day, after work–teaching ESL while a bit hungover was starting to become my baseline condition–I sent Victor another message via Facebook thanking him for the previous night, and asking if he wanted to hang out again. I included my mobile number and asked for his.

That Saturday afternoon, he came downtown and we wandered around Stanley Park, getting to know each other in a much more authentic way. I learned that he was originally from Saskatchewan (as is my father), but grew up in a house just off Commercial Drive and went to Templeton High School; his petite, dark-haired mother had been dead for several years, and he took after her physically; his father, a retired longshoreman, was a big blonde strapping Doukhobor man, making Victor what we in the community shamefully refer to as a “half-breed”; he had attended Emily Carr College of Art and Design (now University); he had been married once; he had no children; he no longer worked for The Sun and was now doing contract art jobs; he used to be a punk back in the day; he painted and painted and painted constantly, as though it were a compulsion. He had spent years as a young man working tough jobs, living in East Vancouver, and toiling away at his art until he landed a gig at The Vancouver Sun as a photo editor and illustrator.

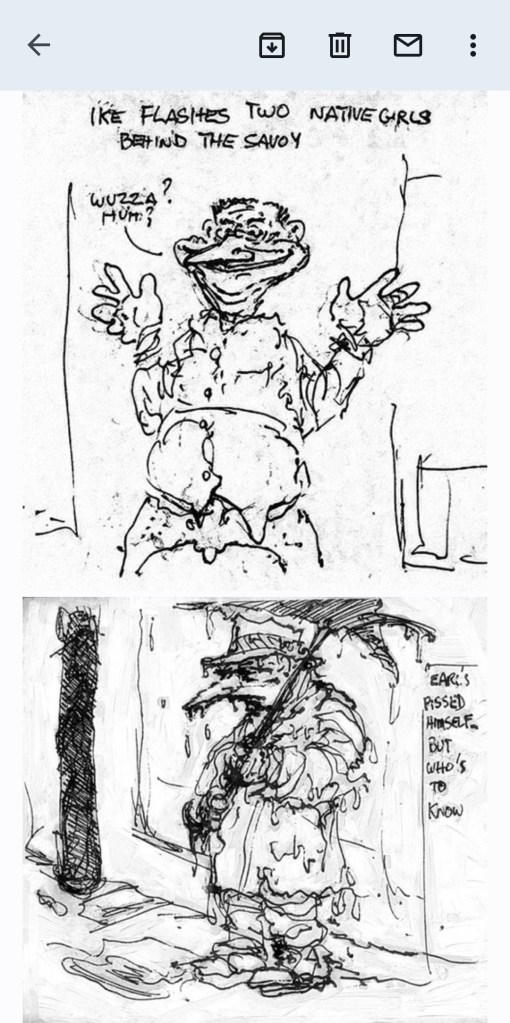

Early 1980s Napkin sketches that Victor did, depicting colourful characters he met in the downtown east side of Vancouver.

We became inseparable after that day. Best friends, comrades, and quite a bit more than that, too.

Victor was nothing like I had imagined him to be. For unknown reasons, I had it in my mind that he was going to be some conservative, stuffy, painfully-serious old newspaper guy who would condescend to me and treat me as less than equal thanks to our age gap. I couldn’t have been more mistaken in my prejudice and unfounded, preconceived notions. He was a capsule of energy, quick-witted and extremely youthful, open-minded and thoroughly nonjudgmental, an enjoyable raconteur and utterly unfazed by anything I said or did, which was a tremendous relief. We once went to the Salvation Army in Kerrisdale, the neighbourhood where he lived and where we spent a great deal of time, and I casually traded the jacket I was wearing for a much nicer one that was on the rack. This was nothing I would consider scandalous, but others perhaps would. The next day, Victor wrote me the following:

I applaud your coat swap. You are indeed a woman of many resources.

I replied:

You, true to form, remain entirely unfazed, and it is one of your greatest qualities.

The first time he invited me over to his place, he said he was going to make me dinner. Having been in many relationships where my partner making me dinner was just slightly less plausible than Canadian Tire money becoming legal currency, I was delighted for the invitation. Little did I know that cooking was not Victor’s forte; in fact, it wasn’t something he did at all. Not much of an eater, his meals consisted mostly of fruit, dried fruit, oatmeal, yogurt, and simple-but-healthy things that took little effort.

When I got to his house, I saw that he was painstakingly–if not painfully–attempting to labour over a curry. “I printed out this recipe I found online,” he said proudly. “I got all of the spices it called for.” Indeed, small bags of various powders were set down on the kitchen counter around him.

“That’s great,” I said.

“Except,” he said, “I realized I didn’t have any salt.”

“No salt?!”

“No. So right before you got here, I ran to the coffee shop I go to all the time and begged them to let me take this from the table.” He picked up a retro-style salt shaker. “They know me, so I told them I’d bring it back tomorrow.”

“How can you not have salt?”

He flashed his Dafoe grin. “I don’t…really cook.”

Predictably, he was so flummoxed by the assembly and preparation of this Indian dish, I ended up taking over and cooking it myself. (This would turn out to be a routine between us, and between me and every boyfriend I have ever had in my life; I am still awaiting the day I meet a man who is adroit and comfortable in the kitchen and can actually put together a decent breakfast, lunch, or dinner for me.)

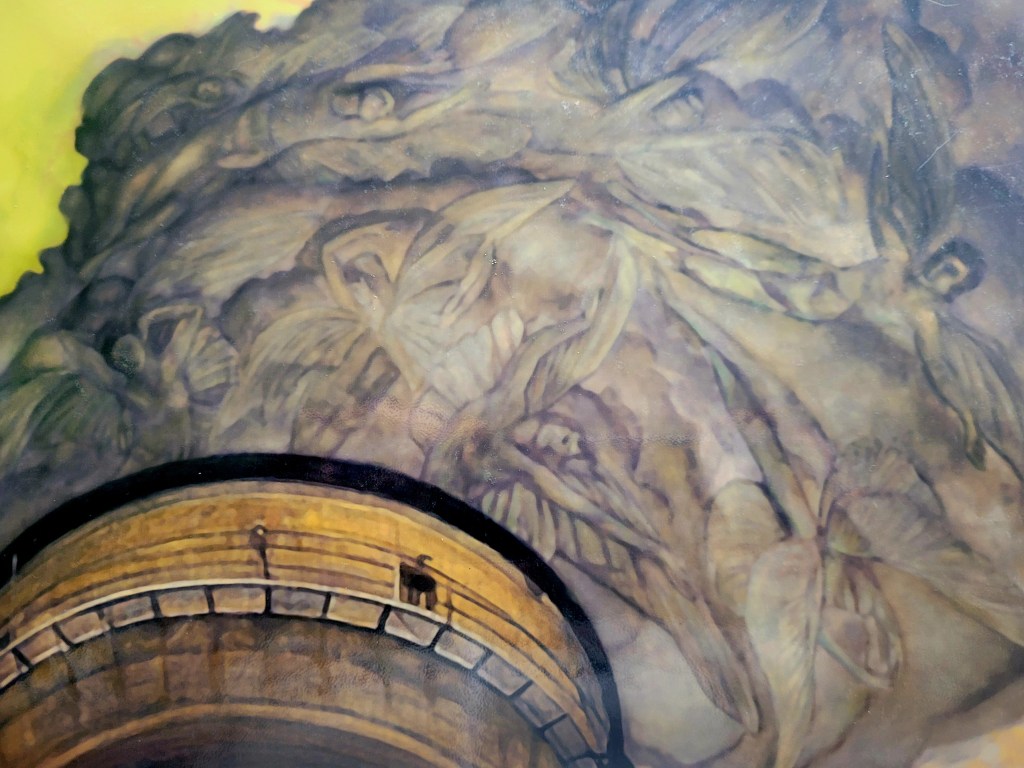

I soon learned that art was Victor’s lifeblood, his oxygen. He spent most of his days creating, drawing, painting, or learning and practicing digital art forms on his computer. He always had paint on his fingers or under his nails, he was always scrubbing his apartment due to endless drips and splatters and messes, and I was stunned when he led me to a big plastic shed on his rooftop balcony and opened it up to show me dozens of paintings. They were all labeled and dated, but simply stacked in there, finished and beautiful and breathtaking and hidden away. Here was this gifted man, working tirelessly all alone in his home studio, and then tucking the finished products into a compartment where nobody could see or admire them. He was, I could see, especially fond of painting angels.

Painting by Victor Bonderoff

I couldn’t understand this hoarding of artistic genius.

“You need an art show,” I told him. “You’re too talented. This is ridiculous.”

Victor agreed, and for the next week or so, we visited some of the galleries along Granville Street between 5th and Broadway to see the displays of Vancouver-based artists and what it would take to get him his own showing. We also spent a Saturday afternoon at the Artwalk in East Vancouver, admiring the crafts and presentations of local creatives. Victor soon handed me a thick book of his work, a physical portfolio of several of his paintings, which I have to this day; it’s how I’ve been able to include many of his works in this blog entry. He never asked for it back, not even when we had to end our friendship, but he had initially given it to me so I’d become more familiar with his output.

The problem, the major hurdle regarding putting on an art show, was that Victor most certainly had the talent and the goods, but he expected me to do basically much of the legwork, serving as his manager, agent, and assistant. I asked him to please create a website that would showcase his pieces, since a digital portfolio was the primary means of familiarizing gallery owners with the collections of any artist. I had absolutely no idea how to build a website, nor was I interested in doing so; he had to take care of his own work, and in turn, I would be happy to cover the managerial and marketing tasks.

Unfortunately, this never got anywhere. He said he would work on a site, but he just…didn’t. I kept trying to push him on this in person, over text, and in emails:

Wish I had the knowledge to help you but unfortunately, I don’t have a clue. My pals Bill and Nev actually create websites and write code for a living BUT…they do it for a living (i.e. they charge…but Bill might throw some free knowledge at me). If you can’t figure it out eventually I can ask for their input…because you gotta sell, Vic!

It seemed that part of him didn’t want to hustle; perhaps subconsciously, he didn’t actually desire any sort of commercial (or even critical) success. He was happy to create, to get his visions out on canvas, but any efforts exceeding that were beyond his ken or interest. The prospect of getting his art out there eventually evaporated, as did our discussions about collaborating on a children’s book about my beloved cat, Annie: I presented him with some first drafts of cleverly rhymed text, while he would be responsible for the book’s illustrations, but instead of going with my stanzas and sketching out some rough drawings to accompany them, he started nitpicking my words and concepts and admonishing me like an editor I never asked for. It was extraordinarily off-putting, and I swiftly shut down the entire concept altogether.

Victor was not capable of collaboration, which he eventually admitted to me:

I hate myself for fuelling your stress. I hope you can forgive me in time. But trust that I am still your ally – I believe in you. I see the talent and creative drive heaving under your sorrow. I see that remarkable lust for life straining against the bonds of your sadness and circumstance. At your best, savvy, sexy, (extremely) funny, deeply spiritual, caring, and sincere. Love you for all of that and more.

A tragedy is that we aren’t bashing our creative talents together. I am convinced we are greater than the sum of our parts. It may be too late. Maybe…..

I thank you for all you have done for me, and yes, you have done plenty for my well-being. It seems I couldn’t do as much for yours….You may not believe it from a middle-aged man, but you have changed me, in some ways quite profoundly.

That’s it for now. Remember somewhere in that stormy brain of yours that I love you without reservation or judgement, whether I see you or don’t. My prayers for the New Year are for you. Get well, dear. And start kicking ass.

Love,

Victor

Friend reading the funnies, by Victor Bonderoff

Still, we were partners in crime, with a connection so organic it seemed as though we were always supposed to be in each other’s lives, and had just been waiting for the other to finally show up. If you’re one who believes in astrological compatibility–which can be great fun to study–his Aries to my Sagittarius meant that we got along seamlessly, happily, innately, always overjoyed to be in each other’s presence.

When his father died that autumn and he revealed this information to me on the bus, his eyes glistening but never spilling over, I wanted to make him feel better despite my expressions of sympathy and empathy, so we made a detour in East Vancouver and I took him to the SPCA to look at kittens and puppies. He was wordlessly grateful, until he eventually did find the words to thank me.

We’d go to live performances and quietly heckle them if they were truly awful, and much of the time, they were. A particular stand-up comedian / local writer with whom I’d gone to SFU was once doing his vastly unfunny bit at the Anza Club, and Victor also knew him from the local arts scene, which he had several connections to. I won’t say the writer’s name, but I hadn’t seen him in over a dozen years and Victor hadn’t seen him in about two, and he had become noticeably rotund, his face ballooning and reddening with each witless punchline.

“The fuck happened to him?” whispered Victor as we slurped our whiskey-cokes. “Is he on doughnuts?”

During the 2015 Christmas season, he took me out for dinner on my 40th birthday, something neither of us ever did (since I usually cooked for us and we were perennially broke, anyway). I bought him a faux-leather thong as a ridiculous Yuletide gift, and Victor loved it: he immediately put it on and spent the entire day and night clad in nothing but the risque underwear, his little buns poking out on either side of the vinyl strip. In return, he gave me Paul Stanley’s memoir, which I had been dying to read.

We also tried going on the Christmas train in Stanley Park one evening that December, but every ride was sold out that night. Disappointed but not defeated, we made our way back along the Seawall, past the historic Vancouver Rowing Club, where it was clear a Christmas party was underway.

“Let’s go in and party and get some food,” I suggested.

“Totally,” he said.

“Just act like we’re supposed to be there.”

We wandered in, neither of us having ever set foot in the vintage building, following the sounds of music and voices to what appeared to be a beautiful, polished-wood ballroom. As cool as you please, we greeted some of the jovial, inebriated attendees, and casually made our way to the buffet table to load up a couple of paper plates with as much chow as they could hold, and walked back out to the Seawall with our impromptu dinner.

We also shared some terminology that both of us couldn’t stop using. He taught me the wonderful “dink hats,” which is how he dismissively referred to baseball caps. I made up “eating pants,” as in Let’s get our eating pants on and scarf down some pizza. He was both revolted and fascinated by such a concept, repeating it anytime we were going to graze on something.

I would spend all of my free time with him, loving him in a form and shape that I hadn’t quite loved anyone before. I can’t say that I was in love with him; it wasn’t entirely a lustful pull in the way that I’ve felt towards other men. It was pure appreciation, admiration, vast relief: I am so glad you exist, Victor, I would think. I am so happy being around you. I am the best version of myself I’ve been in years because of you. I finally found you.

Painting by Victor Bonderoff

* * * * *

Things ended the following spring of 2016, because we went as far as we could go together. We could not become a couple for a few complicated reasons; I was still living with someone, technically, although the relationship was a codependent, unsatisfying farce. The guy I was living with knew I was with Victor all the time–he clearly knew I spent the night at Victor’s place several times–and didn’t care because it meant he had our place all to himself.

When I say my relationship was a farce, I’m not exaggerating. We were both kind of stuck, and I was starting to really unravel thanks to my domestic dysfunction, to being stuck between two men, to my wholly stressful and going-nowhere day job as an ESL teacher, to the deep-down knowledge that I couldn’t be with Victor romantically even if I were single, and to my descent into bona fide alcohol abuse. Once I found myself drinking on the job, gulping down Fireball Whiskey first thing in the morning and then dashing into the staff washroom to glug down even more of it throughout the day, I knew that I was in extremely perilous territory.

The dynamic between me and Victor was starting to go seriously awry; we had taken things to a level and a limit that were unsustainable in the long run, they were getting tense and puzzling, and so I had to break things off with him in order to swing myself back around to some sense of stability. Not long after doing this, I also walked away from teaching ESL forever once I experienced my second terrifying panic attack in the classroom, one that knocked me on my ass so brutally, my school director called the ambulance to haul me to the emergency room at St. Paul’s Hospital.

Two years later, I had kicked out the guy I was living with and felt absolutely adrift, alone, rudderless, anchorless, and completely shaky, unsure of how to function despite being free of someone who had made my life miserable for years. I didn’t seek help; I didn’t quit drinking. In fact, my alcohol consumption had severely escalated by this point and was a source of company and comfort to me. That’s how I saw it, anyway, and would continue to see it for a very long time. I was working from home and isolated and vulnerable, and things would only proceed to get worse for quite some time.

That June of 2018, I (foolishly, desperately) contacted Victor again and he was all too happy to hear from me. We seemed to resume exactly where we had left off, with a few differences: after his father died and all of the details and the will were sorted out, Victor had finally bought himself a modest vehicle after a solo trip to South America. Neither of us had ever really had any real Vancouver-style money before, but him now being mobile was a definite plus when we wanted to hit the North Shore to hike, or south Fraser Street to hit up some of the Indian shops.

Clearly, though, both of us were just a bit more broken than we’d been two years previously. He could see how fragile I was and how much more regularly I was self-medicating with booze; while he’d been happy to imbibe with me before, he had now sworn the stuff off altogether, impressively concentrating on his physical well-being through diet and exercise at the age of 59. I could see, however, that he also wasn’t in a terrific place mentally, being somewhat erratic, raw, and inconsistent with his words and behaviours. There was no future for us. I wasn’t prepared to get swept up with him again so quickly, and in such an intense fashion.

It didn’t take long before everything imploded, except in a sad, sick, completely hostile way. There was no going back to how things had been between us. We had always been more than just close friends, and it was seemingly impossible to believe that we could only ever be platonic.

By the end of August, we were finished. It hadn’t taken long at all. I never spoke to him again. And to be entirely honest: I never wanted to. When I make up my mind about someone or something, it is a Sisyphean task for anyone to attempt to persuade me otherwise. Victor was done.

…and I was history for him. He was a gentle, accepting soul who had never–not once, despite my being very harsh to him on a few occasions–said a single unkind word to me, but he, too, knew that it was better for him that I wasn’t around anymore. I subsequently never thought about him. Never wrote about him. Never saw him. Just kept deteriorating and degrading, and now that I’m thinking about it, perhaps I didn’t ever get hold of him again because I was just so ashamed of what I feel I had devolved into back then. I couldn’t imagine him seeing me in such unspeakably bad shape. He had believed in me so much, I respected and honoured his talent and brilliance and work ethic, and seeing pity on his sweet face would have been more than unbearable.

Victor as a tyke. He sent this to me with the caption, “Even the shoes were too big.”

So seven years later, learning that he’s dead–cancer absconding with Victor around the age of only 65, despite him taking such good care of himself–I’m having a great deal of trouble understanding that he’s just plain gone forever, which is an awfully long time; I have never before lost anyone who was once so dear to me, so close to me, and I don’t ever want to get used to it. That radiant, vivacious, wiry little being full of zeal and humour isn’t in his 1960s walkup apartment in Kerrisdale anymore, painting and listening to music and guzzling coffee and always, always happy to hear from me. I’m having a dickens of a time comprehending his being permanently gone, trying to understand a world without Victor in it, because I keep thinking this: I keep thinking I’ll be able to email him and ask him about it. How was it? What happens? Are there actually angels? Did you see any? Were you scared? Did you see your parents? Were you able to see me, or any of your friends? Did it hurt? Was it like unplugging a TV, or did you travel somewhere? What did everything look like?

And he’d make a joke about it, of course, and then paint all of the things he saw and felt. I keep thinking he’s just gone away for a while. I’ll run into him. I can let him know that I’m doing so much better.

Painting by Victor Bonderoff.

I’m going to leave you with this track, Vic. It’s perfect; it’s you. Do you remember we were supposed to see these guys not long after we first met, but we bailed because neither of us felt like leaving your place and going out? Now, if that doesn’t sum up a couple of hopeless Vancouverites, I’m not sure what does.

Love

Nadya.

Leave a comment